Australian Marine Envenomations PLEASE NOTE: - this page is no longer actively maintained. The information provided may not reflect current treatment guidelines. Resources for this page include "Dangerous Marine Animals of the Indo-Pacific Region" (Carl Edmonds, Wedneil Publications, 1978) and more recently "Venomous and Poisonous Marine Animals" (Williamson, Fenner & Burnett, UNSW Press, 1996), and numerous articles from the Medical Journal of Australia. The ARC guidelines are very useful and the most comprehensive medical review is by Tibbals.

Charmaine Griffiths and Dr. Bruce Livett have a great Cone Shell toxins site. Also I have a brief note on how to remove fish hooks. See also the Jellyfish section of the Australian Venom Research Unit and this article about severe envenomation from the MJA by Peter Fenner and John Williamson The Box Jellyfish - Chironex fleckeri

The Box Jellyfish (also known as the sea wasp or sea stinger) is the only known coelenterate that is lethal to humans. Smaller box jellyfish normally feed on prawns, and larger adults mostly on fish; they are more dangerous to humans. If death occurs, after human envenomation, it can happen within 5 minutes, mostly from acute respiratory failure or acute cardiac arrest. Williamson and Callinan (MJA, Jan 12 1980, pages 13-20) reported that there have been 67 deaths in Australia due to Box Jellyfish envenomation since 1984, though most did not receive modern resuscitation. Systemic effects include confusion, agitation and unconsciousness followed by respiratory failure. The Box Jellyfish is largely invisible in sea water, and may be found in shallow water at the edge of beaches in the Northern Australian and Indo-Pacific region, usually in the hotter months. Its body may weigh as much as two kilograms and has four bundles each with about 10 stinging tentacles, which may extend for up to two metres. In Australia it is generally limited to waters north of the tropic of Capricorn. It is not seen around the Great Barrier Reef. Envenomation is most likely on still summer days, but a review by Fenner showed that severe stings have occured all year round in the Northern Territory, and probably any month except June and July in northern Queensland. When entering the water it is advisable to:

The venom has cardiotoxic, neurotoxic and highly dermatonecrotic components. It is injected by hundreds of thousands of microscopic stings over a wide area of the body and on the trunk. Absorption into the circulation is rapid. Each sting arises from the discharge of a nematocyst. The central rod of the microbasic mastigphore carries the venom, and is like a microscopic spear which is impaled, on contact, into the victim by a springy protein.

Dilute (5%) solutions of simple carboxylic acids such as acetic acid (ie, vinegar) have been shown to totally inactivate nematocysts in about a minute or less. Inactive nematocysts are intact but are prevented from discharging. This is not due to protein denaturation (as formaldehyde, a potent fixative agent, is less effective) and the precise mechanism of inactivation is unclear. Contracted tentacle, however, may conceal some active nematocyts, so complete inactivation is not always possible. The administration of methylated spirits causes nematocyst discharge and hence may worsen the sting, and while it will render exposed parts of the tentacle harmless, it is possible for many nematocysts to remain active. Hence vinegar is preferable for first aid. Management There are two priorities; firstly inactivation (with copious quantities of vinegar) and then removal of remaining tentacle to prevent further envenomation, and secondly management of the envenomation itself. First Aid

Inactivate adherent tentacles by the application, in copious quantities, of vinegar, which prevents further nematocyst discharge by 'fixing' the cells. Do not use alcohol as it will increase discharge. "Stingose" has been shown to be no better than sea water. As little as 30 seconds application of 5% acetic acid will prevent further nematocyst discharge. Most household vinegar is in the range 4.2 to 5.5% and is quite suitable for the task. Remove adherent tentacle - ideally after full inactivation. It is wise to continue to apply vinegar during this process and to use tweezers. Try simple methods of pain relief. Neither vinegar or methylated spirits are useful as analgesics. If antivenom and steroids are available they should be administered as soon as possible. Apply appropriate basic life support should respiratory or cardiovascular failure develop. Medical Management Early administration of Box Jellyfish antivenom is often associated with an immediate improvement in pain and other symptoms and signs. Three ampoules should be diluted 1:10 and injected intravenously as soon as possible. Repeat doses are often required, and should be given according to the clinical circumstances. Ramsay et al have shown, in anaesthetised rats, that pre-treatment with antivenom does not attenuate the immediate hypertensive response but minimises the subsequent cardiovascular collapse, and additionally show that co-administration of MgSO4 with the antivenom enhances its effectiveness. They also noted that maintenance of adequate respiration at all times did not alter the severity of the cardiovascular responses to tentacular envenomation. They had previously shown that the current antivenom does not protect against neuro- and myo-toxicity. Calcium channel blockers show either little or no benefit. Analgesics in traditional doses are usually inadequate to control the pain. Cold vinegar or ice compresses have been advocated as an adjunct. Alcohol increases discharge and should not be used. Topical lignocaine application is often of no benefit, but eutectic lignocaine/prilocaine paste should be tried. Watch out for systemic toxicity in large stings. Heat inactivates the venom itself, but more than 39 degrees centigrade is required. Increasing the temperature and time of exposure enhance antivenom inactivation, but they also increase the risk of burning or scalding, so this may not be a practical therapy. Quoting from Carrette, Cullen et al, "No significant loss of lethality was seen after exposure to temperatures <or= 39 degrees C, even after 20 minutes' exposure. At temperatures >or= 43 degrees C, venom lost its lethality more rapidly the longer the exposure time. Venom was non-lethal after exposure to 48 degrees C for 20 minutes, 53 degrees C for five minutes, and 58 degrees C for two minutes." Where envenomation is associated with systemic signs, this is best managed by the administration of oxygen and sedation, however in severe cases paralysis, intubation, and artificial ventilation should be instituted without delay. Pumonary oedema may occur. Prompt antivenom administration is highly desirable. Death occurs usually in the first 5-20 minutes. Close observation and effective CPR is essential. See also the AVRU Box Jellyfish info pages. Carukia barnesi is a cubozoan jellyfish that can cause envenomation mimicking decompression sickness, with headache, hypertension, severe muscular and abdominal pain, diaphoresis, elevated Toponin I, cardiac dysfunction (visible on echocardiography) and confusion. The appearance is of a hyper adrenergic state. Myocardial injury occurs in about 1/3 of paitents. Systemic magnesium, in slow boluses of 10 - 20 mMol, may attenuate pain and hypotension. Other jellyfish may cause a similar syndrome. See "Irukandji syndrome: a risk for divers in tropical waters", a letter, and "A year's experience with Irukandji in far North Queensland", both from the MJA. Nematocysts can be diagnosed by skin scrapings. These annoying but colurful floating pale blue coelenterates often sting bathers at Sydney beaches when summer afternoon onshore breezes cause them to drift inshore. The stings are painful, and while they may hurt for several hours, no permanent scarring has been reported. Deaths are very rare - none in Australia in comparison to the number of people stung, but at least one in the USA. More information is available from the Australian Museum and the AVRU. First Aid:

The octopus secretes a form of tetrodotoxin in its saliva. This has a selective blocking effect on nerve action potentials. One average sized octopus (weighing 26 grams) has enough venom to paralyse up to 10 adult human beings. No cardiotoxicity has been noted. Fixed dilated pupils may occur as a direct result of the toxin. In the natural state the octopus either secretes the venom in the general vicinity of its prey, waits until it is immobile and then devours it, or else it jumps out and envelops the prey in its tentacles and either bites it or just secretes the venom all around it while it is held. Envenomed patients notice paraesthesia, numbness, tightness in the chest, difficulty breathing and weakness; ultimately respiratory failure occurs, which may lead to death unless adequate resuscitation is instituted. The toxin has a short duration of action, however the onset of complete paralysis may be brief, ie under 10 minutes. If the airway is controlled, ventilation maintained and good intensive care management instituted before cerebral hypoxia occurs, then the outcome should be good. If there are no symptoms of systemic envenomation within 15 minutes of the bite, then usually nothing much happens. If any signs of envenomation develop a firm crepe bandage should be applied, resuscitative equipment and medical assistance obtained if possible, and the patient should be transported with appropriate care to the nearest hospital. Expired air resuscitation should commence if respiratory failure develops, followed by early intubation and ventilation if facilities permit. Sea snakes of the genus Astrotia are are found in Northern Ausrtalian waters and generally are not aggressive, except infrequently during the mating season. Astrokia Stokesii has been studied because it has fangs capable of penetrating a wetsuit. The neurotoxic components of the venom are potent and appear to act on neuromuscular transmission, but only small amounts of venom are usually injected so fatalities are rare. More serious bites involve multiple serrated-edge lacerations. The venom is painless, like that of Australian terrestrial snakes, and this distinguishes sea snake bites from those of other marine creatures in this area. Treatment and general information is the same as for terrestrial snakes - see my pages on snakebite. Firm crepe bandaging should be employed and not removed until the patient is in a suitable hospital. Specific sea snake antivenom is available and tiger snake antivenom may be used in an emergency. See also AVRU. Venomous Fish Stings and Stingray Spine Injuries Non-tropical venomous fish in Australia inlcude catfish, stingrays and the fortescue. In general stings from these cause intense pain and vasoconstriction, the first aid for which involves submerging the affected limb in water that is as hot as can be tolerated (50°C is recommended) until the pain goes away. Take care not to burn yourself with the water (always include an unaffected part of the body in the hot water to 'sense' temperature). If untreated the pain rarely lasts more than 24 hours unless there is a foreign body (a bit of fish spine) retained in the wound or if infection has supervened. Swelling may persist for up to a few weeks and may be associated with a clear watery discharge. Stingray spines are large and may cause significant trauma (one case of pneumothorax has been reported) and, in some cases, considerable local tissue necrosis, which may be best treated by excision. Peter Mayer MD has written a comprehensive review of stingray injuries and treatment thereof - Stingray Injuries: Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, 8, 24-28 (1997). Col Palmer from Melbourne sent me these first-hand experiences with a sting ray spine injury: "Hi there,

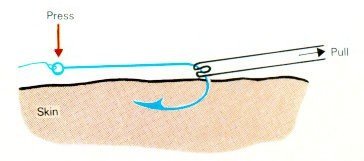

The injury was so severe. The pain was unbelievable! It really was! Thank god it was me and not one of my children, I just would have not known how painful it was. I am a butcher by trade and have been cut/stabbed/sliced and have been stitched by every doctor in Melbourne, so I am quite brave when it come to the pain threshold, but this was something I have never or want to encounter again . The hot water worked really good, but you have to be careful, the pain takes over all the other senses, I couldn't even feel the doctors injections and he gave me heaps of "peth". 30 minutes later I stopped yelling *phew*. But the second worse thing happened for a best part of the week was I was fainting about 10 times a day. The hospital put it down to Marine toxins in my system. The covering of the Stinger is like a slimy velvet (black) and is also pushed into the wound causing mass infection. This MUST be removed ( painfully) I might add. I just thought that I would share my first hand experience with you. Keep up the good work! Regards Colin Palmer." In general, occlusive bandages should not be applied to painful fish stings as they will only make the pain worse. The stonefish is an exception as it contains neurotoxins; in this case if any systemic signs develop a firm crepe bandage should be applied. Stonefish antivenom is available and is effective in reducing pain. If the pain, redness, swelling worsen or if the discharge becomes smelly then infection is likely; if the fish spine has penetrated to bone then osteomyelitis may occur. Medical management involves injection of local anaesthetic for pain control, wound debridement and removal of broken bits of fish spine, dressing with an antibiotic ointment, and observation for signs of infection. Prophylactic systemic antibiotics may be helpful. If a fish hook gets embedded in the skin so that the barb is below skin level, here's a good way to remove it. Local anaesthetic can be helpful but usually isn't needed.

Another way is to push the point of the hook right around until it comes out of the skin via a second wound, then cut the hook with pliers and remove both parts.

Last updated Tuesday, December 04, 2018 |

||

This is one of several known stinging jellyfish of the order Cubomedusae (Phylum: Cnidaria (Coelentera); Class: Cubozoa; Order: Cubomedusae; Family: Chiropidae).

This is one of several known stinging jellyfish of the order Cubomedusae (Phylum: Cnidaria (Coelentera); Class: Cubozoa; Order: Cubomedusae; Family: Chiropidae). When stung, the pain is absolutely excruciating and the victim usually thrashes around in an attempt to get the sting off, which usually has the opposite effect. The tentacles contract, become sticky and adhere tightly. They remain active for some time, hence attempts at removal may worsen the sting and injure the person attempting to do so. Stung areas have a whipped fiery appearance - erythematous, oedematous lines about 0.5 to 1.0 cm wide wherever the tentacle contacted skin, often with a fine white transverse flecking that looks like frost. Severe stings result in blackening and necrosis of the affected skin. Untreated, the pain lasts for days or weeks and healing is poor, usually resulting in permanent scarring.

When stung, the pain is absolutely excruciating and the victim usually thrashes around in an attempt to get the sting off, which usually has the opposite effect. The tentacles contract, become sticky and adhere tightly. They remain active for some time, hence attempts at removal may worsen the sting and injure the person attempting to do so. Stung areas have a whipped fiery appearance - erythematous, oedematous lines about 0.5 to 1.0 cm wide wherever the tentacle contacted skin, often with a fine white transverse flecking that looks like frost. Severe stings result in blackening and necrosis of the affected skin. Untreated, the pain lasts for days or weeks and healing is poor, usually resulting in permanent scarring. This small octopus (

This small octopus ( I was very interested in your article about sting ray stings, as I had the misfortune 2 years ago to be "hit by one of these fellows in the right foot. The stinger went through rubber boots (waders) and when I pulled the waders off, the stinger had pulled my thick white sock through the hole in the waders. The injury has taken 12 months to heal and really to this day I can still feel a sting when I talk about it!

I was very interested in your article about sting ray stings, as I had the misfortune 2 years ago to be "hit by one of these fellows in the right foot. The stinger went through rubber boots (waders) and when I pulled the waders off, the stinger had pulled my thick white sock through the hole in the waders. The injury has taken 12 months to heal and really to this day I can still feel a sting when I talk about it! Thanks to Peter Morton for his advice on how to do this best.

Thanks to Peter Morton for his advice on how to do this best.